by Wayne Grudem

Although several definitions have been given for the gift of prophecy, a fresh examination of the New Testament teaching on this gift will show that it should be defined not as “predicting the future,” nor as “proclaiming a word from the Lord,” nor as “powerful preaching”—but rather as “telling something that God has spontaneously brought to mind.” The first four points in the following material support this conclusion; the remaining points deal with other considerations regarding this gift.

1. The New Testament Counterparts to Old Testament. Prophets Are New Testament Apostles.

Old Testament prophets had an amazing responsibility—they were able to speak and write words that had absolute divine authority. They could say, “Thus says the Lord,” and the words that followed were the very words of God. The Old Testament prophets wrote their words as God’s words in Scripture for all time (see Num. 22:38; Deut. 18:18–20; Jer. 1:9; Ezek. 2:7; et al.). Therefore, to disbelieve or disobey a prophet’s words was to disbelieve or disobey God (see Deut. 18:19; 1 Sam. 8:7; 1 Kings 20:36; and many other passages).

In the New Testament there were also people who spoke and wrote God’s very words and had them recorded in Scripture, but we may be surprised to find that Jesus no longer calls them “prophets” but uses a new term, “apostles.” The apostles are the New Testament counterpart to the Old Testament prophets (see 1 Cor. 2: 13; 2 Cor. 13: 3; Gal. 1: 8–9; 11–12; 2 Thess. 12: 13; 4: 8,15; 2 Peter 3: 2). It is the apostles, not the prophets, who have authority to write the words of New Testament Scripture.

When the apostles want to establish their unique authority they never appeal to the title “prophet” but rather call themselves “apostles” (Rom. 1:1; 1 Cor. 1:1; 9:1–2; 2 Cor. 1: ; 11:12–13; 12:11–12; Gal. 1:1; Eph. 1:1; 1 Peter 1:1; 2 Peter 1:1; 3:2; et al.).

2. The Meaning of the Word Prophet in the Time of the New Testament.

Why did Jesus choose the new term apostle to designate those who had the authority to write Scripture? It was probably because the Greek word prophētēs (“prophet”) at the time of the New Testament had a very broad range of meanings. It generally did not have the sense “one who speaks God’s very words” but rather “one who speaks on the basis of some external influence” (often a spiritual influence of some kind). Titus 1:12 uses the word in this sense, where Paul quotes the pagan Greek poet Epimenides: “One of themselves, a prophet of their own, said, ‘Cretans are always liars, evil beasts, lazy gluttons.’” The soldiers who mock Jesus also seem to use the word prophesy in this way, when they blindfold Jesus and cruelly demand, “Prophesy! Who is it that struck you?” (Luke 22:64). They do not mean, “Speak words of absolute divine authority,” but, “Tell us something that has been revealed to you” (cf. John 4:19).

Many writings outside the Bible use the word prophet (Gk. prophētēs) in this way, without signifying any divine authority in the words of one called a “prophet.” In fact, by the time of the New Testament the term prophet in everyday use often simply meant “one who has supernatural knowledge” or “one who predicts the future”—or even just “spokesman” (without any connotations of divine authority). Several examples near the time of the New Testament are given in Helmut Krämer’s article in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament:

- A philosopher is called “a prophet of immortal nature” (Dio Chrysostom, A.D. 40–120)

- A teacher (Diogenes) wants to be “a prophet of truth and candor” (Lucian of Samosata, A.D. 120–180)

- Those who advocate Epicurean philosophy are called “prophets of Epicurus” (Plutarch, A.D. 50–120)

- Written history is called “the prophetess of truth” (Diodorus Siculus, wrote c. 60–30 B.C.)

- A “specialist” in botany is called a “prophet” (Dioscurides of Cilicia, first century A.D.)

- A “quack” in medicine is called a “prophet” (Galen of Pergamum, A.D. 129–199)

Krämer concludes that the Greek word for “prophet” (prophētēs) “simply expresses the formal function of declaring, proclaiming, making known.” Yet, because “every prophet declares something which is not his own,” the Greek word for “herald” (kēryx) “is the closest synonym.”

Of course, the words prophet and prophecy were sometimes used of the apostles in contexts that emphasized the external spiritual influence (from the Holy Spirit) under which they spoke (so Rev. 1:3; 22:7; and Eph. 2:20; 3:5), but this was not the ordinary terminology used for the apostles, nor did the terms prophet and prophecy in themselves imply divine authority for their speech or writing. Much more commonly, the words prophet and prophecy were used of ordinary Christians who spoke not with absolute divine authority, but simply to report something that God had laid on their hearts or brought to their minds. There are many indications in the New Testament that this ordinary gift of prophecy had authority less than that of the Bible, and even less than that of recognized Bible teaching in the early church, as is evident from the following section.

3. Indications That “Prophets”Did Not Speak With Authority Equal to the Words of Scripture.

a. Acts 21:4

In Acts 21:4, we read of the disciples at Tyre: “Through the Spirit they told Paul not to go on to Jerusalem.” This seems to be a reference to prophecy directed towards Paul, but Paul disobeyed it! He never would have done this if this prophecy contained God’s very words and had authority equal to Scripture.

b. Acts 21:10–11

Then in Acts 21:10–11, Agabus prophesied that the Jews at Jerusalem would bind Paul and “deliver him into the hands of the Gentiles,” a prediction that was nearly correct but not quite: the Romans, not the Jews, bound Paul (v. 33; also 22:29), and the Jews, rather than delivering him voluntarily, tried to kill him and he had to be rescued by force (v. 32). The prediction was not far off, but it had inaccuracies in detail that would have called into question the validity of any Old Testament prophet. On the other hand, this text could be perfectly well explained by supposing that Agabus had had a vision of Paul as a prisoner of the Romans in Jerusalem, surrounded by an angry mob of Jews. His own interpretation of such a “vision” or “revelation” from the Holy Spirit would be that the Jews had bound Paul and handed him over to the Romans, and that is what Agabus would (somewhat erroneously) prophesy. This is exactly the kind of fallible prophecy that would fit the definition of New Testament congregational prophecy proposed above—reporting in one’s own words something that God has spontaneously brought to mind.

One objection to this view is to say that Agabus’ prophecy was in fact fulfilled, and that Paul even reports that in Acts 28:17: “I was delivered prisoner from Jerusalem into the hands of the Romans.”

But the verse itself will not support that interpretation. The Greek text of Acts 28:17 explicitly refers to Paul’s transfer out of Jerusalem as a prisoner. Therefore Paul’s statement describes his transfer out of the Jewish judicial system (the Jews were seeking to bring him again to be examined by the Sanhedrin in Acts 23:15, 20) and into the Roman judicial system at Caesarea (Acts 23:23–35). Therefore Paul correctly says in Acts 28:18 that the same Romans into whose hands he had been delivered as a prisoner (v. 17) were the ones who (Gk. hoitines, v. 18), “When they had examined me . . . wished to set me at liberty, because there was no reason for the death penalty in my case” (Acts 28:18; cf. 23:29; also 25:11, 18–19; 26:31–32). Then Paul adds that when the Jews objected he was compelled “to appeal to Caesar” (Acts 28:19; cf. 25:11). This whole narrative in Acts 28:17–19 refers to Paul’s transfer out of Jerusalem to Caesarea in Acts 23:12–35, and explains to the Jews in Rome why Paul is in Roman custody. The narrative does not refer to Acts 21:27–36 and the mob scene near the Jerusalem temple at all. So this objection is not persuasive. The verse does not point to a fulfillment of either half of Agabus’ prophecy: it does not mention any binding by the Jews, nor does it mention that the Jews handed Paul over to the Romans. In fact, in the scene it refers to (Acts 23:12–35), once again Paul had just been taken from the Jews “by force” (Acts 23:10), and, far from seeking to hand him over to the Romans, they were waiting in an ambush to kill him (Acts 23:13–15).

Another objection to my understanding of Acts 21:10–11 is to say that the Jews did not really have to bind Paul and deliver him into the hands of the Gentiles for the prophecy of Agabus to be true, because the Jews were responsible for these activities even if they did not carry them out. Robert Thomas says, “It is common to speak of the responsible party or parties as performing an act even though he or they may not have been the immediate agent(s).” Thomas cites similar examples from Acts 2:23 (where Peter says that the Jews crucified Christ, whereas the Romans actually did it) and John 19:1 (we read that Pilate scourged Jesus, whereas his soldiers no doubt carried out the action). Thomas concludes, therefore, “the Jews were the ones who put Paul in chains just as Agabus predicted.”

In response, I agree that Scripture can speak of someone as doing an act that is carried out by that person’s agent. But in every case the person who is said to do the action both wills the act to be done and gives directions to others to do it. Pilate directed his soldiers to scourge Jesus. The Jews actively demanded that the Romans would crucify Christ. By contrast, in the situation of Paul’s capture in Jerusalem, there is no such parallel. The Jews did not order him to be bound but the Roman tribune did it: “Then the tribune came up and arrested him, and ordered him to be bound with two chains” (Acts 21:33). And in fact the parallel form of speech is found here, because, although the tribune ordered Paul to be bound, later we read that “the tribune also was afraid, for he realized that Paul was a Roman citizen and that he had bound him” (Acts 22:29). So this narrative does speak of the binding as done either by the responsible agent or by the people who carried it out, but in both cases these are Romans, not Jews. In summary, this objection says that the Jews put Paul in chains. But Acts says twice that the Romans bound him. This objection says that the Jews turned Paul over to the Gentiles. But Acts says that they violently refused to turn him over, so that he had to be taken from them by force. The objection does not fit the words of the text.

c. 1 Thessalonians 5: 19–21

Paul tells the Thessalonians, “do not despise prophesying, but test everything; hold fast what is good” (1 Thess. 5:20–21). If the Thessalonians had thought that prophecy equaled God’s Word in authority, he would never have had to tell the Thessalonians not to despise it—they “received” and “accepted” God’s Word “with joy from the Holy Spirit” (1 Thess. 1:6; 2:13; cf. 4:15). But when Paul tells them to “test everything” it must include at least the prophecies he mentioned in the previous phrase. He implies that prophecies contain some things that are good and some things that are not good when he encourages them to “hold fast what is good.” This is something that could never have been said of the words of an Old Testament prophet, or the authoritative teachings of a New Testament apostle.

d. 1 Corinthians 14: 29–38

More extensive evidence on New Testament prophecy is found in 1 Corinthians 14. When Paul says, “Let two or three prophets speak, and let the others weigh what is said” (1 Cor. 14:29), he suggests that they should listen carefully and sift the good from the bad, accepting some and rejecting the rest (for this is the implication of the Greek word diakrinō, here translated “weigh what is said”). We cannot imagine that an Old Testament prophet like Isaiah would have said, “Listen to what I say and weigh what is said—sort the good from the bad, what you accept from what you should not accept”! If prophecy had absolute divine authority, it would be sin to do this. But here Paul commands that it be done, suggesting that New Testament prophecy did not have the authority of God’s very words.

In 1 Corinthians 14: 30, Paul allows one prophet to interrupt another one: “If a revelation is made to another sitting by, let the first be silent. For you can all prophesy one by one.” Again, if prophets had been speaking God’s very words, equal in value to Scripture, it is hard to imagine that Paul would say they should be interrupted and not be allowed to finish their message. But that is what Paul commands.

Paul suggests that no one at Corinth, a church that had much prophecy, was able to speak God’s very words. He says in 1 Corinthians 14: 36, “What! Did the word of God come forth from you, or are you the only ones it has reached?” (author’s translation). Then in verses 37 and 38, in he claims authority far greater than any prophet at Corinth: “If any one thinks that he is a prophet, or spiritual, he should acknowledge that what I am writing to you is a command of the Lord. If any one does not recognize this, he is not recognized.”

All these passages indicate that the common idea that prophets spoke “words of the Lord” when the apostles were not present in the early churches is simply incorrect.

e. Apostolic Preparations for Their Absence

In addition to the verses we have considered so far, one other type of evidence suggests that New Testament congregational prophets spoke with less authority than New Testament apostles or Scripture: the problem of successors to the apostles is solved not by encouraging Christians to listen to the prophets (even though there were prophets around) but by pointing to the Scriptures.

So Paul, at the end of his life, emphasizes “rightly handling the word of truth” (2 Tim. 2:15), and the “God-breathed” character of “scripture” for “teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness” (2 Tim. 3:16). Jude urges his readers to “contend for the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3). Peter, at the end of his life, encourages his readers to “pay attention” to Scripture, which is like “a lamp shining in a dark place” (2 Peter 1:19–20), and reminds them of the teaching of the apostle Paul “in all his letters” (2 Peter 3:16). In no case do we read exhortations to “give heed to the prophets in your churches” or to “obey the words of the Lord through your prophets,” etc. Yet there certainly were prophets prophesying in many local congregations after the death of the apostles. It seems that they did not have authority equal to the apostles, and the authors of Scripture knew that. The conclusion is that prophecies today are not “the words of God”either.

4. How Should We Speak About the Authority of Prophecy Today?

So prophecies in the church today should be considered merely human words, not God’s words, and not equal to God’s words in authority. But does this conclusion conflict with current charismatic teaching or practice? I think it conflicts with much charismatic practice, but not with most charismatic teaching.

Most charismatic teachers today would agree that contemporary prophecy is not equal to Scripture in authority. Though some will speak of prophecy as being the “word of God” for today, there is almost uniform testimony from all sections of the charismatic movement that prophecy is imperfect and impure, and will contain elements that are not to be obeyed or trusted. For example, Bruce Yocum, the author of a widely used charismatic book on prophecy, writes, “Prophecy can be impure—our own thoughts or ideas can get mixed into the message we receive—whether we receive the words directly or only receive a sense of the message.”

But it must be said that in actual practice much confusion results from the habit of prefacing prophecies with the common Old Testament phrase, “Thus says the Lord” (a phrase nowhere spoken in the New Testament by any prophets in New Testament churches). This is unfortunate, because it gives the impression that the words that follow are God’s very words, whereas the New Testament does not justify that position and, when pressed, most responsible charismatic spokesmen would not want to claim it for every part of their prophecies anyway. So there would be much gain and no loss if that introductory phrase were dropped.

Now it is true that Agabus uses a similar phrase (“Thus says the Holy Spirit”) in Acts 21:11, but the same words (Gk. tade legei) are used by Christian writers just after the time of the New Testament to introduce very general paraphrases or greatly expanded interpretations of what is being reported (so Ignatius, Epistle to the Philadelphians 7: 1–2 [about A.D. 108] and Epistle of Barnabas 6:8; 9:2, 5 [A.D. 70–100]). The phrase can apparently mean, “This is generally (or approximately) what the Holy Spirit is saying to us.” If someone really does think God is bringing something to mind which should be reported in the congregation, there is nothing wrong with saying, “I think the Lord is putting on my mind that . . .” or “It seems to me that the Lord is showing us . . .” or some similar expression. Of course that does not sound as “forceful” as “Thus says the Lord,” but if the message is really from God, the Holy Spirit will cause it to speak with great power to the hearts of those who need to hear.”

5. A Spontaneous “Revelation” Made Prophecy Different From Other Gifts.

If prophecy does not contain God’s very words, then what is it? In what sense is it from God? Paul indicates that God could bring something spontaneously to mind so that the person prophesying would report it in his or her own words. Paul calls this a “revelation”: “If a revelation is made to another sitting by, let the first be silent. For you can all prophesy one by one, so that all may learn and all be encouraged” (1 Cor. 14:30–31). Here he uses the word revelation in a broader sense than the technical way theologians have used it to speak of the words of Scripture—but the New Testament elsewhere uses the terms reveal and revelation in this broader sense of communication from God that does not result in written Scripture or words equal to written Scripture in authority (see Phil. 3:15; Rom. 1:18; Eph. 1:17; Matt. 11:27).

Paul is simply referring to something that God may suddenly bring to mind, or something that God may impress on someone’s consciousness in such a way that the person has a sense that it is from God. It may be that the thought brought to mind is surprisingly distinct from the person’s own train of thought, or that it is accompanied by a sense of vividness or urgency or persistence, or in some other way gives the person a rather clear sense that it is from the Lord.

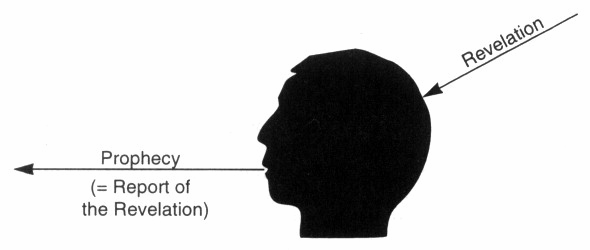

Figure 53.1 illustrates the idea of a revelation from God that is reported in the prophet’s own (merely human) words.

PROPHECY OCCURS WHEN A REVELATION FROM GOD IS REPORTED IN THE PROPHET’S OWN( MERELY HUMAN) WORDS Figure 53.1

Thus, if a stranger comes in and all prophesy, “the secrets of his heart are disclosed; and so, falling on his face, he will worship God and declare that God is really among you” (1 Cor. 14:25). I have heard a report of this happening in a clearly noncharismatic Baptist church in America. A missionary speaker paused in the middle of his message and said something like this: “I didn’t plan to say this, but it seems the Lord is indicating that someone in this church has just walked out on his wife and family. If that is so, let me tell you that God wants you to return to them and learn to follow God’s pattern for family life.” The missionary did not know it, but in the unlit balcony sat a man who had entered the church moments before for the first time in his life. The description fitted him exactly, and he made himself known, acknowledged his sin, and began to seek after God.

In this way, prophecy serves as a “sign” for believers (1 Cor. 14:22)—it is a clear demonstration that God is definitely at work in their midst, a “sign” of God’s hand of blessing on the congregation. And since it will work for the conversion of unbelievers as well, Paul encourages this gift to be used when “unbelievers or outsiders enter” (1 Cor. 14:23).

Many Christians in all periods of the church have experienced or heard of similar events—for example, an unplanned but urgent request may have been given to pray for certain missionaries in Nigeria. Then much later those who prayed discovered that just at that time the missionaries had been in an auto accident or at a point of intense spiritual conflict, and had needed those prayers. Paul would call the sense or intuition of those things a “revelation,” and the report to the assembled church of that prompting from God would be called a “prophecy.” It may have elements of the speaker’s own understanding or interpretation in it and it certainly needs evaluation and testing, yet it has a valuable function in the church nonetheless.

6. The Difference Between Prophecy and Teaching.

As far as we can tell, all New Testament “prophecy” was based on this kind of spontaneous prompting from the Holy Spirit (cf. Acts 11:28; 21:4, 10–11; and note the ideas of prophecy represented in Luke 7:39; 23:63–64; John 4:19; 11:51). Unless a person receives a spontaneous “revelation” from God, there is no prophecy.

By contrast, no human speech act that is called a “teaching” or done by a “teacher,” or described by the verb “teach,” is ever said to be based on a “revelation” in the New Testament. Rather, “teaching” is often simply an explanation or application of Scripture (Acts 15:35; 11:11, 25; Rom. 2:21; 15:4; Col. 3:16; Heb. 5:12) or a repetition and explanation of apostolic instructions (Rom. 16:17; 2 Tim. 2:2; 3:10; et al.). It is what we would call “Bible teaching” or “preaching”today.

So prophecy has less authority than “teaching,” and prophecies in the church are always to be subject to the authoritative teaching of Scripture. Timothy was not told to prophesy Paul’s instructions in the church; he was to teach them (1 Tim. 4:11; 6:2). Paul did not prophesy his lifestyle in Christ in every church; he taught it (1 Cor. 4:17). The Thessalonians were not told to hold firm to the traditions that were “prophesied” to them but to the traditions that they were “taught” by Paul (2 Thess. 2:15). Contrary to some views, it was teachers, not prophets, who gave leadership and direction to the early churches.

Among the elders, therefore, were “those who labor in preaching and teaching” (1 Tim. 5:17), and an elder was to be “an apt teacher” (1 Tim. 3:2; cf. Titus 1:9)—but nothing is said about any elders whose work was prophesying, nor is it ever said that an elder has to be “an apt prophet” or that elders should be “holding firm to sound prophecies.” In his leadership function Timothy was to take heed to himself and to his “teaching” (1 Tim. 4:16), but he is never told to take heed to his prophesying. James warned that those who teach, not those who prophesy, will be judged with greater strictness (James 3:1).

The task of interpreting and applying Scripture, then, is called “teaching” in the New Testament. Although a few people have claimed that the prophets in New Testament churches gave “charismatically inspired” interpretations of Old Testament Scripture, that claim has hardly been persuasive, primarily because it is hard to find in the New Testament any convincing examples where the “prophet” word group is used to refer to someone engaged in this kind of activity.

So the distinction is quite clear: if a message is the result of conscious reflection on the text of Scripture, containing interpretation of the text and application to life, then it is (in New Testament terms) a teaching. But if a message is the report of something God brings suddenly to mind, then it is a prophecy. And of course, even prepared teachings can be interrupted by unplanned additional material that the Bible teacher suddenly felt God was bringing to his mind—in that case, it would be a “teaching” with an element of prophecy mixed in.

7. Objection: This Makes Prophecy “Too Subjective.”

At this point some have objected that waiting for such “promptings” from God is “just too subjective” a process. But in response, it may be said that, for the health of the church, it is often the people who make this objection who need this subjective process most in their own Christian lives! This gift requires waiting on the Lord, listening for him, hearing his prompting in our hearts. For Christians who are completely evangelical, doctrinally sound, intellectual, and “objective,” probably what is needed most is the strong balancing influence of a more vital “subjective” relationship with the Lord in everyday life. And these people are also those who have the least likelihood of being led into error, for they already place great emphasis on solid grounding in the Word of God.

Yet there is an opposite danger of excessive reliance on subjective impressions for guidance, and that must be clearly guarded against. People who continually seek subjective “messages” from God to guide their lives must be cautioned that subjective personal guidance is not a primary function of New Testament prophecy. They need to place much more emphasis on Scripture and seeking God’s sure wisdom written there. Many charismatic writers would agree with this caution, as the following quotations indicate:

- Michael Harper (Anglican charismatic pastor): Prophecies which tell other people what they are to do—are to be regarded with great suspicion.

- Donald Gee (Assemblies of God): Many of our errors where spiritual gifts are concerned arise when we want the extraordinary and exceptional to be made the frequent and habitual. Let all who develop excessive desire for “messages” through the gifts take warning from the wreckage of past generations as well as of contemporaries. . . . The Holy Scriptures are a lamp unto our feet and a light unto our path.

- Donald Bridge (British charismatic pastor): The illuminist constantly finds that “God tells him” to do things. . . . Illuminists are often very sincere, very dedicated, and possessed of a commitment to obey God that shames more cautious Christians. Nevertheless they are treading a dangerous path. Their ancestors have trodden it before, and always with disastrous results in the long run. Inner feelings and special promptings are by their very nature subjective. The Bible provides our objective guide.

8. Prophecies Could Include Any Edifying Content.

The examples of prophecies in the New Testament mentioned above show that the idea of prophecy as only “predicting the future” is certainly wrong. There were some predictions (Acts 11:28; 21:11), but there was also the disclosure of sins (1 Cor. 14:25). In fact, anything that edified could have been included, for Paul says, “He who prophesies speaks to men for their upbuilding and encouragement and consolation” (1 Cor. 14:3). Another indication of the value of prophecy was that it could speak to the needs of people’s hearts in a spontaneous, direct way.

9. Many People in the Congregation Can Prophesy.

Another great benefit of prophecy is that it provides opportunity for participation by everyone in the congregation, not just those who are skilled speakers or who have gifts of teaching. Paul says that he wants “all” the Corinthians to prophesy (1 Cor. 14:5), and he says, “You can all prophesy one by one, so that all may learn and all be encouraged” (1 Cor. 14:31). This does not mean that every believer will actually be able to prophesy, for Paul says, “Not all are prophets, are they?”(1 Cor. 12: 29, author’s translation). But it does mean that anyone who receives a “revelation” from God has permission to prophesy (within Paul’s guidelines), and it suggests that many will. Because of this, greater openness to the gift of prophecy could help overcome the situation where many who attend our churches are merely spectators and not participants. Perhaps we are contributing to the problem of “spectator Christianity” by quenching the work of the spirit in this area.

10. We Should “Earnestly Desire”Prophecy.

Paul valued this gift so highly that he told the Corinthians, “Make love your aim, and earnestly desire the spiritual gifts especially that you may prophesy” (1 Cor. 14:1). Then at the end of his discussion of spiritual gifts he said again, “So, my brethren, earnestly desire to prophesy” (1 Cor. 14:39). And he said, “He who prophesies edifies the church” (1 Cor. 14:4).

If Paul was eager for the gift of prophecy to function at Corinth, troubled as the church was by immaturity, selfishness, divisions, and other problems, then should we not also actively seek this valuable gift in our congregations today? We evangelicals who profess to believe and obey all that Scripture says, should we not also believe and obey this? And might a greater openness to the gift of prophecy perhaps help to correct a dangerous imbalance in church life, an imbalance that comes because we are too exclusively intellectual, objective, and narrowly doctrinal?

11. Encouraging and Regulating Prophecy in the Local Church.

Finally, if a church begins to encourage the use of prophecy where it has not been used before, what should it do? How can it encourage this gift without falling into abuse? For all Christians, and especially for pastors and others who have teaching responsibilities in the church, several steps would be both appropriate and pastorally wise: (1) Pray seriously for the Lord’s wisdom on how and when to approach this subject in the church. (2) There should be teaching on this subject in the regular Bible teaching times the church already provides. (3) The church should be patient and proceed slowly—church leaders should not be “domineering” (or “pushy”) (1 Peter 5:3), and a patient approach will avoid frightening people away or alienating them unnecessarily. (4) The church should recognize and encourage the gift of prophecy in ways it has already been functioning in the church—at church prayer meetings, for example, when someone has felt unusually “led” by the Holy Spirit to pray for something, or when it has seemed that the Holy Spirit was bringing to mind a hymn or Scripture passage, or when giving a common sense of the tone or the specific focus of a time of group worship or prayer. Even Christians in churches not open to the gift of prophecy can at least be sensitive to promptings from the Holy Spirit regarding what to pray for in church prayer meetings, and can then express those promptings in the form of a prayer (what might be called a “prophetic prayer”) to the Lord.

(5) If the first four steps have been followed, and if the congregation and its leadership will accept it, some opportunities for the gift of prophecy to be used might be made in the less formal worship services of the church, or in smaller home groups. If this is allowed, those who prophesy should be kept within scriptural guidelines (1 Cor. 14:29–36), should genuinely seek the edification of the church and not their own prestige (1 Cor. 14:12, 26), and should not dominate the meeting or be overly dramatic or emotional in their speech (and thus attract attention to themselves rather than to the Lord). Prophecies should certainly be evaluated according to the teachings of Scripture (1 Cor. 14:29–36; 1 Thess. 5:19–21).

(6) If the gift of prophecy begins to be used in a church, the church should place even more emphasis on the vastly superior value of Scripture as the source to which Christians can always go to hear the voice of the living God. Prophecy is a valuable gift, as are many other gifts, but it is in Scripture that God and only God speaks to us his very words, even today, and throughout our lives. Rather than hoping at every worship service that the highlight would be some word of prophecy, those who use the gift of prophecy need to be reminded that we should find our focus of joy, our expectation, and our delight in God himself as he speaks to us through the Bible. There we have a treasure of infinite worth: the actual words of our Creator speaking to us in language we can understand. And rather than seeking frequent guidance through prophecy, we should emphasize that it is in Scripture that we are to find guidance for our lives. In Scripture is our source of direction, our focus when seeking God’s will, our sufficient and completely reliable standard. It is of God’s words in Scripture that we can with confidence say, “Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path” (Ps. 119: 105).